George Ayittey is a profoundly dangerous man. He was thrown into prison in Senegal in 1994. After his release, he was trailed across Africa by government men. Regimes around the world have banned his works. He is forbidden from television appearances. His offices were raided and ransacked, then later firebombed.

His crime is a simple sentence: “Africa is poor because she is not free.”

Ayittey is undeterred: today he heads the Free Africa Foundation, a Washington-DC based think tank fighting for political reform. He most recently endeared himself to autocrats all over the world by writing in his latest book, Defeating Dictators, “The only good dictator is a dead dictator.”

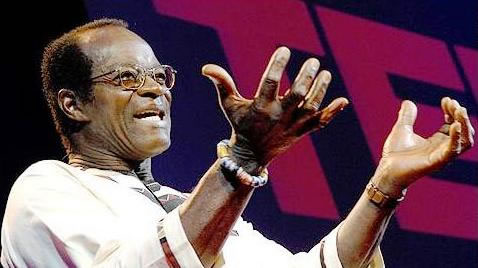

Ayittey, from Ghana, combines a razor-sharp intellect with bombastic activism, making him a one-man wrecking-ball against tyranny everywhere. Though an economist by training, Ayittey sets his economic expertise alongside a thorough understanding of African history. And he sets them both against Africa’s modern political order.

The Tradition of Liberty in Africa

His first book, a dense, 500-page tome titled Indigenous African Institutions, is sarcastically dedicated to “the reeducation” of “African Leaders and Elites.” Like anywhere else, the people of Africa have struggled for their entire history to contain violence and snuff out tyranny in their societies. Ayittey’s book is a riveting look at how they accomplished this and is a useful corrective to the fantasy that the West “discovered” liberty and free-markets.

Many African groups were essentially Stateless, and organized themselves using consensual, bottom-up decision making. Even where groups lived in a hierarchy like a Kingdom or Chiefdom, political leaders were strongly restrained by elaborate systems of checks and balances and a long-standing emphasis on the rule of law: “traditional African ‘laws’ were not mischievously decreed by the chief or king in collusion with a platoon of soldiers. Customary laws were subject to full public debate … chiefs and kings could not promulgate laws without the concurrence of councils” (72). When public outcry wasn’t enough, the final check was the power of exit: people who felt oppressed led exoduses away from their leaders.

Ayittey explodes the myth that Africa before colonization was purely a land of hunter-gathers and subsistence farmers, arguing instead that trade, free movement, and free association were paramount. Miners, craftsmen, and cottage industry organized into elaborate, decentralized networks of guilds (283). Contrary to Western misperceptions, “In indigenous Africa, all the factors of production were owned by the natives, not by their rulers, the chiefs, or by tribal governments” (284). Prices were free-floating and not fixed by chiefs and kings (339-340). Free trade and free movement dominated, “there were no ‘borders’, goods and people moved freely across Africa. Today, modern African leaders man artificial borders with uniformed bandits and decry the same activity as ‘smuggling’” (355).

Africa Betrayed

Ayittey argues that these institutions partially survived colonialism, despite the heavy-hand of Western administrations. Though some areas fared better than others, many Africans still arbitrated their disputes using traditional courts and laws as well as trading widely in informal markets (396-406).

As exploitative as colonial powers were, Ayittey believes that the real tragedy of African development came with ‘independence.’ “The freedom that Africans fought for from colonialism was perfidiously betrayed,” he charges, “True freedom and development never came to much of Africa. Independence was in name only. One set of masters (white colonialists) was replaced by another set (black neo-colonialists) and the oppression and exploitation of the African people continue unabated.”

Often with the covert and sometimes open assistance of the West, African governments have embarked on a series of debacles Ayittey calls “Swiss-bank Socialism” and “Coconut Democracy.” Under socialism, African leaders have terrorized their country’s people, raped the continent’s natural resources, and drove economies into the ground. But leaders and their cronies ship off the plunder to their own Swiss-Bank accounts. Some African leaders have stolen more wealth from Africa during their time ‘in office’ than the entire net worth of all US presidents – from Washington to Obama – combined.

Under “Coconut Democracy”, African states uphold a farcical system of elections to keep up a semblance of political legitimacy. But fraud and vote-rigging mar the process. The paper ballots mean little without a free press and with government and crony-capitalist monopolies dominating the economic system. Both of these political orders Ayittey terms “Vampire States” because they “suck the economic vitality of their people.”

Africa’s Cheetah Generation

Ayittey believes the answer to fighting off Africa’s predatory leaders and unleashing rapid economic growth in the process lies in the continent’s indigenous institutions. Western development ‘experts’ are naïve to think that they can retrofit Western institutions on to an entirely different people. This is absolutely not to say that Africans are somehow unable to grow the elaborate commerce networks enjoyed by the West. Ayittey believes that free commerce, free movement, free association, and free speech are the true heritage of Africa, as reflected in their indigenous institutions. The trouble lies in bringing the superstructure of Western parliaments and executives and artificially dropping them on an different evolved social order: one that relies on kinship, community and custom more than the individualistic West.

Indeed, where Africa enjoys its greatest economic growth, employment, and innovation is in the areas where indigenous institutions rule. The vast majority of Africans work in the ‘informal sector’, a term for the sprawling grey and black markets that sustain life for most of the population. Except for raids and incursions for extortion by political elites (sometimes euphemistically called “State-led development projects”), these markets exist on the periphery of Africa’s many cities, outside the reach of its formal political institutions. But the commerce is far from peripheral. The economic activity in these markets – which is not including illicit substances like drugs or weapons – is worth trillions of dollars and is Africa’s largest employer.

Ayittey believes that we should turn to the informal sector and build on Africa’s traditional institutions. The “Hippos” of Africa – Ayittey’s term for sour bureaucrats and corrupt operators that hamper progress – can only be overcome by its “Cheetahs”. The Cheetahs are a new breed of “angry young African”, intelligent, savvy, motivated, and pragmatic. Where the Hippos see a social problem demanding bureaucracy, Cheetahs see a business opportunity. They are institution builders for the future: working in the informal sector and creating a quiet revolution of entrepreneurial projects that fill the chasms left by malicious government. They bring new technology and expertise. They set up co-ops and mutual-aid. They run profitable enterprises. They, and not the leaders at the podium, are the proper heirs to Africa’s heritage of liberty.

Earlier this month, SFL launched a new section of their website for African Students for Liberty. Those interested in free-markets and free people cannot afford to be unfamiliar with George Ayittey. He’s an eloquent spokesman for the oppressed, in Africa and elsewhere. His words make dictators squirm in their seats – and that alone should be testament to the power of Ayittey’s ideas.