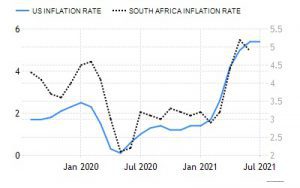

We frequently come across the term “inflation.” In March 2020, we saw governments and central planners around the world shut down the economy in response to the global pandemic. This was subsequently followed by a global recession, with 3 million jobs lost after the first month of lockdowns, businesses closed, and livelihoods lost. Many governments swiftly reacted by providing unprecedented amounts of stimulus checks flowing directly into citizens’ bank accounts, as well as other forms of economic relief. This was followed by a sharp rise in consumer prices, not just in the US, but in emerging markets like South Africa as well.

Source: tradingeconomics.com

Year-over-year July CPI in South Africa came in with a 4.9% increase. Month-over-month CPI posted a 0.2% gain. In the US, the official inflation rate remains at 5.4%. Despite these significant inflation numbers, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) & other central banks around the world, still claim that any major increases in consumer prices will likely be “transitory”.

Economists & other macro insiders have been going back & forth on Fin-Twit, debating whether inflation will be transitory, or secular, sustained price increases over the long term. The answer to that question requires us to look at the inflation story in terms of probabilities, not certainties.

In the first quarter of 2020, the SARB announced its plan to purchase government treasury bonds in an attempt to provide liquidity in the secondary market and to artificially suppress interest rates. This process is called Quantitative Easing (QE). The SARB purchased approximately R1 Billion worth of Treasuries in March, R11 Billion in April, R10 Billion in May, and R5 Billion in the month of June. Despite such heavy figures in the context of the South African economy, it pales in comparison to the size of QE conducted by other central banks like the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and Bank of England.

When primary dealers buy treasuries, their deposits with the commercial bank decreases – as well as the commercial banks’ reserve balance (their asset). What happens to the government account?

There is a vast misconception around the world of finance that QE increases the money supply. This myth is founded on the baseless assumption that the central bank “prints money” to buy treasuries from primary dealers. This could not be further from the truth. Central banks can only “print” bank reserves out of thin air, not broad money. Only commercial banks create money out of thin air, through the process of credit creation. The only way QE can expand the money supply is when the SARB purchases those treasuries from non-bank primary dealers. These counter-parties do not have reserve accounts with the SARB, however, they have deposit accounts in the commercial banking system.

It’s important to note that bank primary dealers have reserve accounts with the SARB, which is an asset of the bank primary dealer, and liability of the SARB. When the SARB conducts QE with bank primary dealers, they credit the primary dealers’ reserve account with new bank reserves that the SARB creates out of thin air. Since the SARB took treasuries off the primary dealer’s balance sheet in exchange for new bank reserves, this means that the primary dealer has more bank reserves and fewer treasuries on their balance sheet. It is simply an asset swap, from the perspective of the primary dealer. This is not money printing. It is only “printing” bank reserves, which isn’t even broad money.

When the SARB conducts QE with non-bank primary dealers, the story is significantly different. Non-bank primary dealers have deposits, which they hold as assets, but are liabilities of the commercial bank they have an account with. The commercial bank has an equivalent asset to back these deposits. This asset is called bank reserves. The SARB purchases those treasuries by crediting the reserve account of the commercial bank that the primary dealer has an account with. As the commercial bank has more bank reserves, they also need to increase the deposit account of the primary dealer, so that the balance sheet matches.

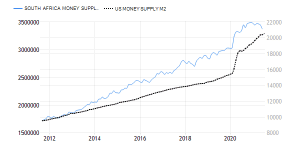

The process of doing QE with non-bank primary dealers expands the money supply because these dealers do not have reserve accounts with the SARB. That’s the key difference between banks and non-bank primary dealers. Most primary dealers are non-banks, which explains why South Africa’s money supply increased by 14% in 2020 alone.

Source: tradingeconomics.com

Source: tradingeconomics.com

In order for this process of QE to take place, primary dealers have to buy the treasuries that government issues on auction. When primary dealers buy treasuries, their deposits with the commercial bank decreases – as well as the commercial banks’ reserve balance (their asset). What happens to the government account? The government has a checking account with the SARB, which is an asset of the government and liability of the SARB. The government’s account increases when primary dealers buy treasuries from the government at auction. This is how the government is able to fund grants and other stimulus programs.

Many economists and financial analysts claim that the recent spike in consumer prices is caused by supply chain disruptions, which should be resolved as the global economy fully re-opens. The problem with this argument is that it fails to acknowledge the root cause of the recent supply chain disruptions. There are countless factors that influence supply chains, however, the main reason is due to excess demand for goods, thanks to worldwide government stimulus programs.

If we get more fiscal spending from the government getting deeper into debt, with the SARB monetising the debt through QE, inflation is most likely here to stay for a very long time. If government stimulus comes to an end, we could possibly see disinflation, or even worse, a deflationary bust.

Written by Tumisho Ramodisa. He is the co-founder of Equity Kings, an investment firm based in Johannesburg. He is also the host of ‘The Wealth Show With Equity Kings’ podcast. Follow him on Twitter @Nxture_Boi.

Photo by Clive Surreal on Unsplash.

Very informative and helpful