In the 1700s, the gold rush in southeast Brazil created a high demand for mining labour. The Minas Gerais region became one of the main destinations for African slaves. For the first half of the century, demand was met by a trade circuit connecting the ports of the Bight of Benin to Salvador in Bahia.

People from those ports acquired a reputation among the Portuguese as the best hands for mining gold.

With time, they created a commercial system of slave classification. Many Africans were grouped with the understanding that they are naturally suited for certain jobs. Slaves were sorted by anatomy and the purported ability to function better in certain climates, resistance to diseases, and life expectancy. Based on this classification, they were either assigned to the fields or less rigorous housework.

This process of stereotyping was unwittingly aided by many Africans with body markings. The markings represented aspects of their lives. They were commonly scarification marks, tattoos and cuts. These indicated their identities, ethnicity, religious affiliation, life events, accomplishments and social status.

Sometimes they were made to obtain spiritual protection. Others were permanent beauty marks. These meanings were lost to the Portuguese. They used them simply to profile and identify slaves. The markings also helped to recapture escaped slaves and ensure slaveholders paid taxes.

In my study of colonial archives, I researched how physical attributes shaped the way Africans were viewed. Race relations in Brazil are generally thought of in terms of multiple skin colours categories associated with various interethnic relationships. But its largest enslaved population consisted of Africans. So, it is important to understand how colonial society dealt with their diversity of origins to construct blackness.

Slavery in Brazil did not, in fact, automatically erase the diversity of African origins and reduce people to one racial category – ‘Black’. It happened over time.

The slave economy

In the Brazilian regions where gold and diamonds were mined, slave ownership was taxed. The tax office began listing slaves’ Christian names, ages, origins, purchase price and body markings in official registries. They also put this information on the identification cards that slaves had to carry with them. Scarification was then used as a marker of the person’s homeland.

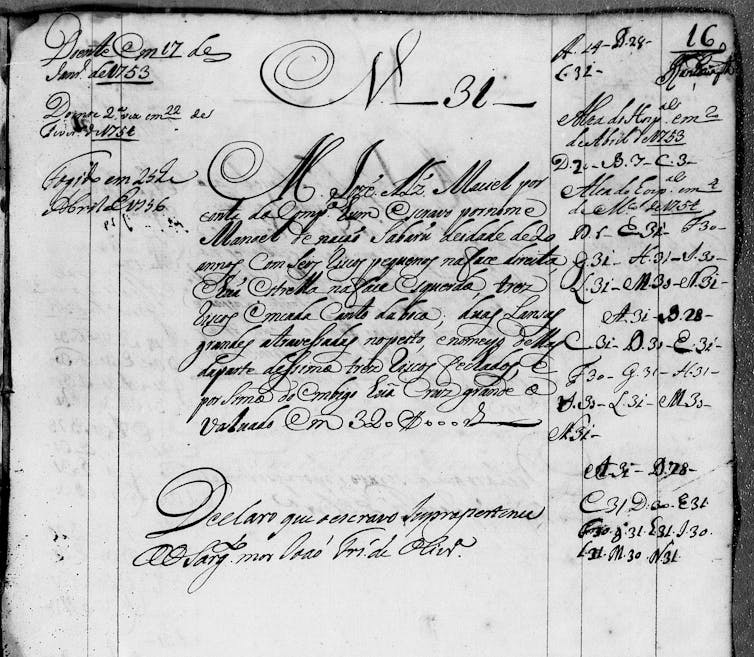

Here’s a description I found from 1752:

“Domingos Sabarú, 20 years old, with smallpox pockmarks, and four small spears on top of his right eyebrow, two circles on top of the left eyebrow, a small grid in the middle of the eyebrows, a star at the temple in the corner of his right eyebrow and the more signs that are on every face of Sabarú, valued at 300 thousand réis”. (Sabarú is currently Savalou, Benin).

Arquivo Público Mineiro, Matrícula de escravos.

These colonial interpretations of African scarifications oversimplified their original meanings. In several regions, their meanings went far beyond ethnicity or origin. In West Africa, some skin patterns express religious affiliation with specific entities of the hierarchy of gods and deified ancestors called voduns in the Gbe-speaking area or called orishas in the Yoruba territories. In these cases, marking were acquired as part of the rites of initiation.

Other markings are records of significant events such as a death in the family. They can also symbolise belonging to a complex multi-levelled society. These marks indicated an individual’s age, medical history, and their social, political and gender-related status. Some marks are formed from the injection of medicines and substances believed to offer protection from unseen forces. Some were just creative expressions.

Brazil represented almost half of the entire Atlantic trade. Its 18th century colonial society never saw Africans as homogeneous people. Nor was the African body classified solely on the basis of skin colour. Identity was formed as a combination of body modifications and phenotypical traits, or physical attributes.

African diversity and blackness

The Portuguese colonialists were concerned with commerce and social control. They saw body markings as tools for identification and cataloguing, to increase the economic efficiency of commodified human lives.

In addition to body marks, clerks also habitually described anatomical features. The hair texture, skin tone and nose shape of individual Africans were recorded and contrasted with European features.

In the end, the same gaze that used visual markers to categorise the diversity of African origins eventually lumped them together in a simplified idea of ‘blackness’. But one did not exclude the other. They were two facets of the same process that transformed Africans into ‘Blacks’.![]()

Aldair Rodrigues is adjunct assistant professor at Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

First appeared in The Conversation.

Photo Credit: PBS.